Drafting a novel on art.

2nd October, 2021

I wrote ‘The Curse of the Matsumoto Cherrywood’ around ukiyoe and there’s a lot to think about.

‘The Curse of the Matsumoto Cherrywood’ is a story with ukiyoe (Japanese woodblock prints) at its heart. The Floating World prints are often billed as a representation of ‘real’ life, but that version of reality was mediated by the explosion of popular culture that flowed from the end of protracted civil war, new systems of administration and technology, and a wider distribution of wealth.

These days life is seen through a digital lens. Slo-mo, high-def, 16-bit, megapixel cameras deliver uncountable versions presenting candied snaps of self within #InsertAdjective life-stories. It’s a fiction created by us for us, a mass-culture, a global economy, a social experiment of twenty-year longitude. We edit these pictures before publishing, colouring our world in the manner we wish to project.

Crosby, Google search ‘Insta selfie’, 2020.

Since early in the twentieth century, phenomenologists considered the relationship of the self to the phenomena of the world. One could discover the self by studying the way one sensed the things about–a kind of comparison of me to it. Visual art is a record of the historical changes of this perception. The vision of the Renaissance, Neo-Classicism, Impressionism, Post-Modernism or in Japan, Tosa, Rinpa, Kano could be described as a culture’s selfie, that is, a construction of reality. Using the innovation of oil paint, Renaissance painters glorified the gods and their patrons with lush portraits while much of Europe starved. The discovery of buried relics in Italy and Greece drew the aristocratic 18th century Neo-classical eye to cool marble antiquities, their cousins the Romantics created narratives around the associated mythology, morality and political discourse of ‘those fab-halcyon days’ while women fought for suffrage.

John Turnbull, Romantic Landscape, 1783.

All these schools placed the privileged viewer at the centre by using Brunelleshi’s perspective experiment of the early 15th century when he drew a grid on a mirror to chart the lines of recedence. But glass mirrors were not seen in Japan until the Dutch brought them in the late 18th century, by which time systems of depicting symbol and narrative were very well established.

Utamaro Kitagawa, Woman looking at her face in mirror, c. 1800.

The religious stories of Chinese Buddhism used natural phenomena like trees, rocks, rivers and mountains as symbols of philosophy and devotion. Receiving that influence, the Japanese art movements such as

Tosa…

Tosa Mitsuoki, Kashiwagi – Tales of Genji, 16th century.

Kano…

Kano Eino, Birds and Flowers of Spring and Summer, latter half of 17th century.

Rinpa…

Ogata Korin, Irises at Yatsuhashi Bridge, 1709.

provided a method of representation and arranging the phenomena of the real world in two-dimensional space in a uniquely Japanese way. Western perspective drawings and paintings came to Japan from the early 18th century in Dutch traders, but were largely rejected by local artists who preferred, rather than to adhere slavishly to the vanishing point with its individualistic viewing mode, to create schemes of representation with meaningful placement of symbolic objects. Kennichi Sasaki explains the eastern concept of removing middle-ground, often lost in mist, to give a sense of energy or ki to the landscape. He links ukiyoe to received Chinese traditions of sansui (mountain + water), in which human figures are subsumed by their surrounds.

Sesshū Toyo, Folding screen landscape, Muromachi period.

Masters such as Hiroshige and Hokusai in the early 1800’s experimented with western linear perspective, incorporating both systems of representation… castles float among expansive clouds, Mt Fuji floats above, while common people struggle between cramped lines below.

Hokusai Katsushika, Nihonbashi bridge in Edo, 1830

色相Colour

The Tokugawa Shoguns ruled from 1603 to 1856 turning an eastern fishing town into a city of one million residents called Edo (Tokyo). Many of them read books, looked at posters and bought clothing from catalogues. Halfway through the 18th century, when the demand for printed books reached 100,000 per-year, when post-print colour-wash posters advertised the latest kabuki theatre or calendars asked readers to guess the short and long months of the year, a more efficient means of bringing colour became necessary.

It’s a sign of my utter disorganisation in drafting that I advanced so far with the first draft of ‘Cherrywood’ before I considered the innovation of colour. Victoria Finlay’s book ‘Colour, travels through the paintbox’ shows the far-flung places that the western masters sourced their brilliant colours. The use of colour in Japanese art is no less important to the development of its culture, and when I examined my association with ukiyoe, I realised that the ‘floating world’ that beckoned to me was singing in tones of pigment. In my story ‘Cherrywood’, colour-print technology is conceived by divine inspiration given to a single artist–but the truth is always more prosaic. A collective approach was necessary in woodcut printing, as publisher, designer, carver and colourist created efficiencies in production. It makes sense therefore that though Suzuki Harunobu is credited with the first colour (calendar) print in 1764…

Harunobu Suzuki, Colour woodblock print. Parody of the Three Vinegar Tasters, with (left to right) Ono no Komachi, Yang Guifei and perhaps Murasaki Shikibu respectively replacing Laozi, Buddha and Confucius. Picture calendar (e-goyomi) for the year 1766 (Meiwa 3); date indicated by the numbers in the two bands around the jar. British Museum.

that the technology that made this possible was developed in collaboration over time. Registration of different colour passes on the one sheet was crucial, so a carver it must have been that invented the kento tabs for the paper to sit justified between blocks; no doubt a colourist, who had worked on after-print washes to then, drank tea… mm, more likely saké, with some paper suppliers and was offered a sheet of of hosho paper, which was strong enough for repeated rubbings. And the pigments themselves were of no concern, as vegetable pigments were popular from lipstick to lacquerware.

Writing box and brush with mountain landscape scene, Japan, Edo period, 19th century, gold lacquerware, Cincinnati Art Museum

The publisher found a merchant to sponsor the enterprise and the artist Harunobu was called to design. It’s important for magic realism not to lose sight of the real bit. So while I read of the recurring theme of the ‘divine boy’ in shinto texts, who might have provided the singular inspiration I desired, I researched the actual use of colour. Not till the turn of the 19th century did imported mineral pigments such as the Prussian blue seen in Hokusai’s ‘The Great Wave of Kanagawa’ or in ‘Nihonbashi Bridge’ (above) come to be used. Before that time, safflower made red, dayflower blue, amur cork or turmeric yellow, ground shells white and lamp soot made black with rice starch to thicken and apply the mix. Some of these, particularly the safflower and dayflower are extremely sensitive to light, and so many of 18th century prints display colour faded, changed or absent.

Utamaro Kitagawa, Flowers of Edo: Young Woman’s Narrative Chanting to the Samisen, 1800

I took this cultural fantasy of Edo for the mis-en-scene of the first part of Book 1 of ‘Cherrywood’ and relieved it with some of the more gritty truths that are available in many of the excellent English accounts, for example by Timon Screech on foreign influence, or Nishiyama Matsunosuke on Nihonbashi culture, or Yabuta Yutaka’s paper on the women of Edo. Understanding both the real life and the way Edoites wished to see themselves was important for my story because ukiyoe was where I commenced the writing. I must accept that the poor reader, only has my say so, and though I take that responsibility with care, I must also follow my heart in the telling. Harunobu’s prints of courtesan’s holding kimono closed against the wind,

Harunobu Suzuki, Girls at the shore, 1765-70. British Museum.

Hiroshige’s exquisitely composed postcards of famous touring spots

Hiroshige Utagawa, Back View of Mt.Fuji from Dream Mountain in Kai Province, 1852.

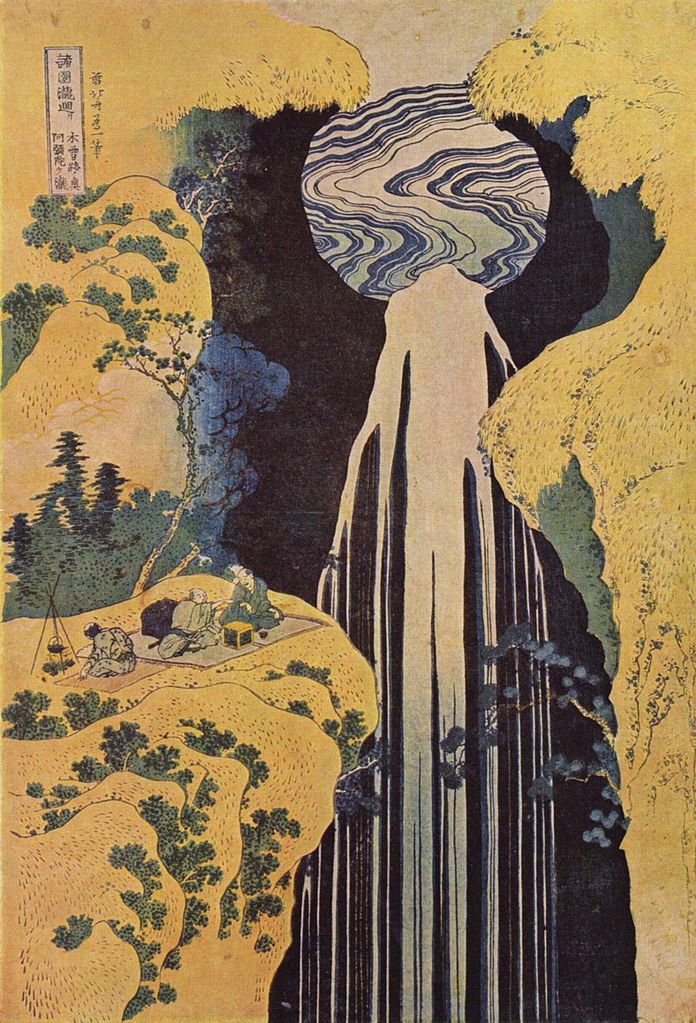

Hokusai’s transcendent representations of nature

Hokusai Katsushika, The Amida Falls in the Far Reaches of the Kisokaidō, 1832.

these were views not just looking through the roof upon court scandals, or ancient mythologies on gold-leaf screens, but depicted all facets of society. Ultimately all we have left, Japanese or foreigner, are the second or third-hand accounts interpreted by writers and these mass-produced snapshots to understand how central was the appreciation of culture in Edo, and how widespread its influence in projecting the identity Japan wished for itself.

Wonderful article with a ton of great info!

utagawa kuniyoshi

LikeLike

it is indeed! 🙂

LikeLike